Residencia

RESIDENCIA |

|

The Residencia is a hotel for staff and guests at the European Southern Observatory's Paranal Observatory in northern Chile. Located in an extremely remote and desolate section of the Atacama desert, the Residencia was designed by the German architecture firm Auer + Weber as a sanctuary in an environment that has never supported life. The L-shaped building was dug into the ground as if to conceal its presence, presenting profoundly different faces depending on the approach. From the road entrance out front the Residencia is practically invisible; from the observatory on the mountain's top all that's seen is the skylight dome. And from the open desert the building could be a mirage: a long, flat brick wedged between two hills like a step into the star-filled sky. Auer + Weber's primary design challenge was to create an oasis for Paranal's staff who work under severe conditions (night shifts, extended isolation from family and friends, harsh weather). The site is not unlike an Antarctic or science fiction lunar colony -- a lonely outpost in a hostile, inhuman terrain. Auer + Weber's solution was to integrate the building into the surrounding landscape while subduing the desert's harsh edges by creating long, cavernous public spaces that echo the openness of the desert, enclosed by dark earth tones that produce a cozy and secure effect. A swimming pool in the central atrium provides humidity to counteract the dehydrating pressure of the desert air and doubles as an exercise outlet. There are trees and plants throughout the building that surprisingly give refuge to birds who have managed to nest alongside the astronomers. Though the desert outside looks like Mars, the interior spaces provide the kind of relaxed luxury that feels like the pinnacle of Earth-based civilization. A few years ago the Residencia was featured as the bad-guy lair in the James Bond movie QUANTUM OF SOLACE and it's easy to see why. Like the best Bond architecture, there's an impossible quality to the building that asks how such a strange luxury could exist in so barren a desert. In the end, though, the Residencia was designed for astronomers, not megalomaniacs, for people working for the sake of humanity and not to exploit it. It feels right then that such work can be supported by so marvelous and serene a place. At dusk automated shades on all the windows close to prevent light leakage that would disrupt the nearby observatory's work. There are always reminders that this is a place for work. Inside, sealed off from the alien desert, busy preparations for the night's activities: conversations over dinner in the cantina; reviewing emails in the lobby; checking data in the archives. Outside, except for the wind, is silence. The horizon, like the sky above, is a darkening mystery. Sit on the terrace and watch the sun set behind mountains of red dirt and dream of other worlds. |

|

| ESO website |

PARANAL OBSERVATORY |

|

The Paranal Observatory is one of the world's leading astronomical research facilities, a complex of ten massive telescopes operated by the European Southern Observatory (ESO). Located 2,600 meters (8,600 ft) above sea level in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile, Paranal looks like something out of science fiction. It is both literally and figuratively an outpost on the frontier of civilization, of the human experience. ESO chose this remote site for its clear, dark skies and stable atmospheric conditions -- what's known as good "seeing" -- as well as for the perspective of the night sky the southern hemisphere provides. It feels like a gateway from our world to another, which in many ways it is. "There's no cause for alarm" we hear over and over from computer speakers -- the nerdy in-joke of the workplace. "But there probably will be." Where work takes place in the night is something essential. Here, the office chatter is a babel of languages: Spanish, English, French and German. What are they talking about? Gaussian flux, red-shifts, scalar fields… we don’t understand. A group of astronomers are talking about Mars. We’re delighted by the irony of people spending all their time peering deep into space at places that probably look exactly like where they are. But when we find out later that one of these astronomers is actually part of the NASA team landing the next Rover there and is at Paranal for last-minute atmospheric observations, we feel dumb. Outer space is closer than we think. |

|

| Paranal Observatory website |

KANAZAWA PHONOGRAPH MUSEUM |

|

The Kanazawa Phonograph Museum is one of those only-in-Japan kind of places -- a narrow devotion, an idiosyncratic labor of love that over time acquires an institutional heft to make it seem totally normal and obvious. "Of course there'd be a museum like this!" you say to yourself after spending some time inside but once you leave you begin to wonder if you'd really been there, whether such a place actually exists. In the museum’s listening room we listen to what Mr. Yokaichiya claims is the first Japanese recording, a scratchy Meiji-era tune sung at the dawn of the Taisho. He plays it on a self-changing player -- a kind of prototype jukebox -- that once belonged to the emperor. Did the emperor himself listen to this record on this turntable? And what is the song? Who performed it? With Mr. Yokaichiya as the dj, there's no better way to experience this sonic trip back in time packed with all its attendant mysteries. Mr. Yokaichiya changes the record. Bing Crosby worries "… it scares me that tomorrow / someone else else may take my place." David Toop, in his fantastic book SINISTER RESONANCE, writes how sound -- intangible and transitory -- is a haunting. A close listener is "like a medium who draws out substance from that which is not entirely there." These old sounds -- the warble of a shamisen, the crackling spoken word of a news report -- emerge here out of polished mahogany speakers like a seance, echoes from the past. Surrounded by all these instruments that conjure voices out of vinyl discs and cylinders, the experience is both eerie and exhilarating.

|

|

| Kanazawa Phonograph Museum website |

UMIMIRAI LIBRARY |

|

Umimirai Library is a public library in the western part of Kanazawa, a slow 20-minute drive from the city center. Designed by Coelacanth-K&H Architects, an architecture firm based in Tokyo, and opened in June 2011, the three-story self-described “cake box” was intended to invigorate this sleepy area of town, a low-lying neighborhood of dreary houses and big box stores that lacked any hubs of activity or real public space. But ask the man on the street about it and you’ll most likely encounter a blank. We inquired at the Tourism Center for directions and even they had to google it. Apparently, not much happens in this part of town -- not yet at least, which is sort of the point of the library. The building is a large white box perforated with hole-punched windows that light up the interiors naturally in the day and at night glow out like portholes of a giant ship. There is a maritime feel to the place, probably unintended, or maybe since it was designed by a firm whose name evokes the ancient deep sea the contrary feelings of floating and drifting and being submerged are all by design. We could easily imagine how much we’d love coming here if this were our local, an airy place with soft, diffused light that lends room to learn, daydream, and to remember. Song lyrics echo in the mind: “...and our friends are all aboard / many more of them live next door...” It’s a peaceful, sublime place, this literary submarine. The main reading room with its 40-foot ceilings provides a grand scale that all great libraries have, from the NYPL on Fifth Avenue to Suzzallo on the University of Washington campus. In fact, we liked Umimirai so much more than that other notable library in Seattle -- Rem Koolhaas’ central library -- a dazzling structure, no doubt, but a place that’s more like a puzzle than a place to retreat. Once you get past the spectacle of its punctured skin, the Umimirai Library is a comfortably traditional place. It’s no wonder the library is filled with young children, the elderly, and students -- a library’s most loyal patrons. Sure there are modern features like glassed-in cellphone booths and self-service checkout stations. But we were most envious of the spacious newspaper reading room -- an old man’s joy -- with its canted desks, localized lighting, and drawers full of past days. Japan is a nation where the newspaper is still very much a part of everyday life, and that Coelacanth featured this reality underscores the success of its design and their intent to insinuate the library into the community’s daily activities. For us, so much about Japan feels like a bizarro alternate reality where -- like with the newspaper that’s disappearing everywhere else -- the rest of the world moves right while Japan turns left. This library feels no different. These days, investing in a new library seems like a counter-intuitive act where, at least in the U.S., branch libraries close one-by-one and already meager budgets continue to be slashed. It’s impossible, laughable even, to imagine our cramped Chinatown branch being replaced by the gleaming Umimirai Library ... which says everything about this library and this town and why we love Japan so much. It feels like a luxury that a space like this was newly built, a sign that that the city believes in its people, that believes the act of reading is worth investing in, that believes these things will continue to matter in the future and that it’s important for these people and activities to come together in an inspiring and provocative space.

|

|

| Umimirai Library website |

21st CENTURY MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART |

|

The 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art (21CM) is located in Kanazawa, a small arts-minded city on the western coast of Japan. Opened in 2004, the museum occupies a prime position in the city center, across the street from not only City Hall but also the old castle and Kenrokuen, one of the loveliest gardens in all of Japan. When you spend some time in Kanazawa, 21CM’s central location makes sense: the geography, the building’s circular form, and the steady traffic streaming throughout the space all suggest the 21CM as a community hub in this charming town by the sea. The museum was designed by SANAA, an architecture firm now very much celebrated around the world, whose reputation was earned from projects like this. Similar to Gehry’s Guggenheim in Bilbao, the 21CM has had a transformative effect on this provincial city off the Tokyo-Kyoto-Osaka shinkansen axis. Not only has the museum placed Kanazawa on the map for the world’s art travelers, more importantly, it gave residents another way to imagine their town, as a place that matters beyond its traditional prefectural boundaries. The seriousness of the museum’s ambitions are further bolstered by the strength of its exhibits, hosting shows by foreign artists like Matthew Barney and Gerhard Richter as well as by some of our favorite Japanese artists like Takashi Homma and Makoto Saito. For a small city, it’s an incredible opportunity to experience the work and ideas from such a wide range of people. Architecturally, the museum is a cluster of box-like galleries unified by a circular shell. SANAA has compared it to a series of islands, an archipelago, and the way we experience the space very much has that feel of circulating water. It’s clear the museum’s design explores some of the dominant issues in Japanese architecture – the binary tension between public-private, inside-outside, decentralization, geometry, ambiguous space, etc. And much has been said about the round building’s de-centered approach, which is all true. You can enter the building from four different directions depending on where you are in the neighborhood and each port will influence how you experience the space. It’s like the flip side to SANAA’s Moriyama House in Tokyo -- a similar group of segmented structures open to its surroundings -- but this museum, as a public space, feels more dynamic and complete, inviting and impressive. We spent a couple months in Kanazawa not too long after the museum first opened and always loved visiting, stopping by once or twice a week for lunch in the café, to thumb through architecture books displayed on Atelier Bow Wow’s fantastic manga-pod, to gape at the abyss of Anish Kapoor’s optical mystery or just to sit in the quiet of the James Turrell room. Our favorite space, though, was the library, a place to browse through current issues of Japanese and international art magazines and to research the works of artists you think about as you wander the museum or through the town itself. Its glass walls make the space so inviting, where you can watch the changing light outside and all the activity passing through the museum itself. The nearby galleries reserved for kids and community projects are always full, with children on school-sponsored field trips romping through, pensioners, young couples on dates, office workers on lunch breaks -- it makes you feel like you’re in the heart of the city. Kanazawa is a town whose beauty and primary attraction is from its past and how well it has managed to preserve it. Never bombed in the war, it’s the town we always imagined Kyoto would be, and there are many neighborhoods where it’s easy to lose yourself in time and forget which century you are in. Still, you know from the name alone that the museum is not preoccupied with this past. Instead, what makes the 21st Century Museum so special and meaningful is how confidently it thinks about the present and the future, not by locking itself in the sentimental prison of history but by showing how art and architecture can help you understand all of this and still provide a way to make you feel connected to it all. |

KAIKARO |

SAZANAMI FISHING COOPERATIVE |

|

Sazanami Fishing Cooperative operates out of Nanao, Japan, a small fishing village located at the base of the Noto Peninsula on the Sea of Japan. The waters off the peninsula contain some of Japan’s richest source of fish; we visited in January which happened to be buri (yellowtail) season, a fish that marks the winter throughout the country. We stayed at a nearby ryokan where every single dish we were served for dinner featured buri in some form or another. It gave us a good idea of what we’d see in the morning. We arrived at the docks at 4am long before sunrise. Men huddled around fires burning in steel barrels like hobos waiting to catch out. The cooperative is made up of a wide-range of hard men and restless high school boys still unsure of their futures. Traveling out to the open waters with them we got the feeling we were witnessing the arc of a local man’s life. Live by the sea, die by it. The Noto seemed like the kind of place where little changes over time. Soon the young men on the boats will become old and the cycle of life will repeat itself in a way people in cities now like to call ‘sustainable’ but is really just the way things are done and always have been. Like that cycle we learned too that the benefit of joining a commercial fishing expedition was the chance to consider the food chain up close. For us, the sea has always been a magical mystery, so full of unseeable things blanketed beneath the water’s surface. Over the course of the morning we would see everything we’d been eating during our time in Japan -- yellowtail, squid, octopus, mackerel. The way the fish emerged out of the dark waters was like a gift or prize or theft, a reward that felt illicit since we’d done nothing to deserve it other than to be there. We were told there would be stink but we never noticed it. We were warned about seasickness but were too excited to ever feel the boat’s motion. Seeing the catch of fish felt important the way visiting a farm is for a child -- to learn where things come from -- a small lesson, perhaps, underscored by the embarrassment that we’d never attempted to observe this process before. To a city dweller, life out by the sea always feels somehow simpler -- a dumb fallacy, of course. It’s not so much simpler as it is more elemental: water, cold, darkness, speed. It’s a compressed experience, one where everything feels identifiable and known even if the elements are never under control or really understood. It’s an experience that stays with you -- you think you’re right to eat this way, a sea-based diet, even as you’re confronted with the unlucky mass of sea life struggling in the net, with the pile of dying fish, with the ultimate randomness of the catch itself. The sea and everything that comes out of it, the men who work in the dark to extract fish from sea, are all a revelation that will be remembered forever. |

3331 ARTS CHIYODA |

|

3331 Arts Chiyoda is a community arts organization based in Akihabara, Tokyo. Housed in a converted junior high school building, 3331 runs a large exhibition gallery on the ground floor where curators and other creatives are invited to stage shows and events not typically seen elsewhere in Tokyo. It also offers an artist residency that provides housing for visiting artists from around the world, a rare opportunity to live in the center of Tokyo. Tokyo is not known as a city with wide public support for the arts but 3331 looks to counter that history. Founded by a group of artists who all have a long history with public art practices, 3331's mission is to make art a more familiar part of the everyday. The former school building is owned by the local Chiyoda ward administration and leased to 3331 at below-market rates in order to provide public space for the local community. 3331 serves as landlord for the building, managing and renting out offices and gallery spaces to other arts organizations, from children's arts workshops to the internationally-renown graphic design magazine +81, among others. It's a nice place to go for a visit: walk through the hallways to see what's going on, eat lunch at the ground-floor cafe, or have a coffee and cigarette in the grassy courtyard out front. Like all galleries and museums, the art on display may not always suit your sensibilities but you can be sure to engage with something at this busy, vibrant center. |

|

| 3331's website |

PHOTOGRAPHERS' LABORATORY |

|

Photographers' Laboratory is a film processing and printing studio in Akasaka, Tokyo owned by Toshio Saito. For decades, Saito has worked closely with some of the most widely known fine art photographers in Japan. In 1974, he printed much of the work on display at MoMA's landmark "New Japanese Photography" show, the first major exhibition about Japanese photography outside of Japan that included photographers like Daido Moriyama, Shomei Tomatsu, and Masahisa Fukase, among others. Today, Saito continues to work with many of these same artists in addition to new generations of fine art and commercial photographers who seek out his expertise. We visited Photographers' Laboratory on a sweltering day in September, grateful for the cool recess of its basement location. The lab is a cluster of cramped rooms loaded with decades' worth of equipment and machines. Watching Saito and his assistants at work, it was unavoidable to think how their work becomes increasingly obscure even as the popularity of photography grows exponentially. Fewer and fewer people will ever see the inside of a darkroom or have their photographs printed by hand. A sad reality for sure. And we rued only too late the irony of documenting the lab's work with a digital camera, an act -- using the instrument of their demise -- that seemed ruder and ruder as each person asked, "digital?" But perhaps Photographers' Laboratory offers an antidote to technology's rush to make the past obsolete. By specializing in the upper reaches of his craft, Saito's future is possibly safer than most, or at least the horizon still distant. Or, more simply still, perhaps he's less concerned with these uncertainties as he just continues working the way he best knows how. |

|

| Photographers' Laboratory's website |

GEORGE NAKASHIMA WOODWORKER |

|

George Nakashima Woodworker is a custom furniture company located in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, owned by siblings Mira and Kevin Nakashima. Founded by their father, George Nakashima (1905-1990), in 1947, the nine-acre site served as a kind of laboratory for integrated living, testing George's concepts of "decentralization, intermediate technology and living off the land" while synthesizing his varied experiences in the Pacific Northwest, Japan, and India, among other places. Today, it continues as an active woodworking studio as well as a heritage center preserving George's legacy. It is, above all, an exceedingly serene place. We were fortunate to visit on a day Mira was hosting a client and tagged along as they went through the careful process of selecting wood, a singular experience that probably best begins to distinguish the Nakashima studio. Divided among three buildings, the bulk of Nakashima's wood collection is stored in an enormous barn-like warehouse where lumber is horizontally stacked in the boule form of the log. Here, there are slabs and lumber that date back to George's early days in Bucks County, awaiting a project for which they'd be bested suited. Here, it's easy to remember the "soul of the tree," the elemental foundation that guides the studio's operation. It's easy, too, to settle into the rhythm of the studio, especially shaded under the towering oaks from the late summer sun. Everywhere is the sound of work: the buzzing of saws, the sander's squeal, the percussive thump of tools and machines that signal things are being made. And in the moments when work pauses, crickets -- or are they cicadas? -- while Mira's young grandson swims in the pool at the forest's edge. A day at Nakashima's is a powerful testament to George's legacy, that the work we do and why we do it is inseparable from how we do it. It's a legacy worth preserving and one Mira both guards and extends by continuing to evolve the studio's work in the spirit her father laid out. |

|

| Nakashima's website |

OUTLIER: MAKING OF A SHIRT, PART 10 OF 10 |

|

[Reviewing finished shirt; concluding thoughts about the shirt] Outlier is a clothing company owned by Abe Burmeister and Tyler Clemens, based in Brooklyn, NY. See WORKING: OUTLIER for further information. |

OUTLIER: MAKING OF A SHIRT, PART 9 OF 10 |

|

[Production: sewing] Outlier is a clothing company owned by Abe Burmeister and Tyler Clemens, based in Brooklyn, NY. See WORKING: OUTLIER for further information. |

OUTLIER: MAKING OF A SHIRT, PART 8 OF 10 |

|

[Production: cutting fabric] Outlier is a clothing company owned by Abe Burmeister and Tyler Clemens, based in Brooklyn, NY. See WORKING: OUTLIER for further information. |

OUTLIER: MAKING OF A SHIRT, PART 7 OF 10 |

|

[What is a marker? reasons for using Gambert for production instead of Nancie] Outlier is a clothing company owned by Abe Burmeister and Tyler Clemens, based in Brooklyn, NY. See WORKING: OUTLIER for further information. |

OUTLIER: MAKING OF A SHIRT, PART 6 OF 10 |

|

[Fabric shopping; sales model; challenges of selling online versus retail; pricing difficulties] Outlier is a clothing company owned by Abe Burmeister and Tyler Clemens, based in Brooklyn, NY. See WORKING: OUTLIER for further information. |

OUTLIER: MAKING OF A SHIRT, PART 5 OF 10 |

|

[Gambert Shirt Factory; Tyler reviews sample shirt and compares to Nancie's sample; discusses production logistics] Outlier is a clothing company owned by Abe Burmeister and Tyler Clemens, based in Brooklyn, NY. See WORKING: OUTLIER for further information. |

OUTLIER: MAKING OF A SHIRT, PART 4 OF 10 |

|

[Mailing; fifth shirt fitting; shirt sizing; laying out shirt on a marker; discussing production cost estimate with Nancie; considering another factory for production] Outlier is a clothing company owned by Abe Burmeister and Tyler Clemens, based in Brooklyn, NY. See WORKING: OUTLIER for further information. |

OUTLIER: MAKING OF A SHIRT, PART 3 OF 10 |

|

[Tyler describes Outlier's business structure; picking up t-shirts from factory and preparing them for shipping; button sewing on to shirt sample; fourth shirt fitting] Outlier is a clothing company owned by Abe Burmeister and Tyler Clemens, based in Brooklyn, NY. See WORKING: OUTLIER for further information. |

OUTLIER: MAKING OF A SHIRT, PART 2 OF 10 |

|

[Second shirt fitting; what is a pivot sleeve?] Outlier is a clothing company owned by Abe Burmeister and Tyler Clemens, based in Brooklyn, NY. See WORKING: OUTLIER for further information. |

OUTLIER: MAKING OF A SHIRT, PART 1 OF 10 |

|

[First shirt fitting; introduction to shirt and Outlier's working process; Abe explains production relationship with Nancie.] Outlier is a clothing company owned by Abe Burmeister and Tyler Clemens, based in Brooklyn, NY. See WORKING: OUTLIER for further information. |

WORKING is a series of short videos profiling the practices of small, owner-operated businesses. Inspired by Studs Terkel's landmark oral history of working people in the early 1970's, WORKING interviews individuals who have rejected the idea of working for others, instead setting up businesses in order to work for themselves. If Terkel's study triumphed the survival of the human spirit against the daily humiliation of the Job, the individuals presented here update that theme with personal examples of autonomy against the economies of scale that perpetuate the demoralized workplace. WORKING attempts to highlight the successes of these individuals in carving out ways to live, of tailoring a "work" situation that "works" for them, offering up business models that value independence over financial and/or material preoccupations. Terkel, quoting a union leader: "Once we accept the concept of work as something meaningful -- not just as the source of a buck -- you don't have to worry about finding enough jobs." WORKING seeks to learn about the actual practice and challenges of running a business by asking specific questions of how things are done. WORKING tries not only to look behind-the-scenes but also to consider self-assessments regarding the successes and failures of the respective business practice. Ultimately, we hope the profiles inspire you to do it yourself. Note: WORKING is interested in businesses which are rooted in physical spaces (e.g., offices, studios, storefronts) instead of freelance situations that can be transported city to city. The physical nature of these businesses demonstrates, at the least, a commitment to the city where their practice occurs, something increasingly important in stemming the homogenization and scaling of our cities and of unifying the strange divide between where we live and where we work. |

OUTLIER |

|

Outlier is a clothing company owned by Abe Burmeister and Tyler Clemens, based in Brooklyn, NY. Since they produced their first garment — pants — in 2008, Outlier has carved out a niche in two highly-saturated markets: fashion and cycling. Their company tag line, “tailored performance,” refers to their primary inspiration and motivation as urban bike commuters. From pants, they’ve worked to expand a line of clothes they consider “future classics,” incrementally adding to their catalog rather than reinventing itself each season like traditional fashion companies who release new products while discontinuing previous ones. Outlier in some key ways is a departure for the WORKING series. Only Tyler currently works full-time for the company and they have yet to establish a permanent, dedicated physical office. Regardless, we were drawn to Outlier’s story because it underscores so many of the challenges involved in running a small business, especially in New York City. Because they produce locally, we were particularly curious to see how their production process worked when so much of New York’s once mighty garment industry has been offshored and lost. Visiting the garment district today is a clear reminder of that past; it still remains a hive of small-business activity, albeit smaller and less visible. Our visits with Outlier over the course of six months to the garment district showed us a network of small businesses, a microcosm of the city at large with its layers of interdependencies. As they will readily acknowledge, Outlier is a business born of and reliant on New York’s resources. Outlier proves how despite knowing little about clothing, good ideas and resourcefulness can go a long way in establishing a business. And still, Outlier represents a paradoxical bind many manufacturing companies face who market a “local” brand while depending on the internet for sales. In some ways, Outlier has no choice but to use the city’s garment factories. Because their mission of “tailored performance” promises a base-level of quality and because their production runs are relatively small, what cost savings that may be gained by offshoring production are minimal at best. Local garment factories, only a bike ride away, can be easily monitored and more importantly, relations easily formed. A paradox, however, emerges on the income-earning end of Outlier’s business, where the retail industry’s standard mark-up structure makes traditional sales outlets cost-prohibitive for small businesses that operate on already slender margins. And so while being able to locally produce high-quality goods, Outlier finds itself unable to fully benefit from the abundance of New York’s retail street scene. Instead the company experiences a strange inversion of globalization’s supply chain by boasting of a hyper-localized manufacturing system while having to depend on the internet’s placeless-ness for sales. That said, for small companies like Outlier, while it makes good sense — business, personal, political even — to produce everything locally, we wonder how long this production model can be sustained. Already, in the course of our filming, Outlier’s locale expanded, slightly yet meaningfully, across the Hudson River into New Jersey. And while this WORKING video series likes to champion the local guy, we will be very interested to track their growth to see how new challenges affect their business model. As it stands, we think the situations Outlier currently tackle are highly intriguing and compelling. The video posted here is a short trailer for a much longer feature-length profile documenting the development and production of a garment — a shirt. The full-length feature learns about Outlier by observing the company at work, following Abe and Tyler as they figure out how to make a shirt that meets their own exacting standards. Much of the time is spent on location at the garment factories they collaborate with to design and produce their clothes. By focusing attention on a specific product and showing some of the unseen effort that constitutes its development, this next edition of WORKING hopes to offer a nuanced and complicated look at the practices of a small business. |

|

| Outlier's website |

DEPOT |

|

Depot Cycle & Recycle is a bicycle shop in Ichikawa, an eastern suburb of Tokyo a little more than an hour's bike ride from Shibuya. Established by Seiya Minato in 2001, Depot first began by offering bike parts and accessories to Tokyo's far-flung messenger community. Seiya made his mark too by importing many foreign brands into Japan, introducing companies like ReLoad and Freitag to Tokyo's cyclists while encouraging local producers to develop their own products. Seiya presaged Japan's street trend of fixed-gear track bikes and for years was the only Tokyo-area bike shop selling used keirin frames, working with local frame builders to resell retired bikes. Now that the trend has exploded into a media-recognized phenomenon, spiking prices to unaffordable levels, Seiya has concentrated more on encouraging bike culture, the "things around the bike," as he puts it. "I'm not so interested in the bike... I like riding bikes." We talked to Seiya about running a store and was particularly curious about why he was way out in Ichikawa when shop after shop was springing up in central Tokyo, feasting off a scene he helped develop. "We were born here," he explained, "we should do it in our place. It is our reality." If you spend an afternoon at Depot you will meet all sorts of people: shoppers, messengers, neighborhood residents, and certainly his two young daughters, Aika and Yume, and his wife, Mami, who may be nursing their newborn son. It is a kind of, er, hub for a community that responds positively to Seiya's infectious energy, generosity, and kindness. And then it becomes clear that Depot was never about scenes but about the strength and sincerity of relationships. Like the best kinds of bike shops all around the world, it is a community service. |

|

| Depot's website |

POSTALCO |

|

Postalco is a stationery and leather goods company based in Tokyo and owned by Mike and Yuri Abelson. They moved to Tokyo in 2001 from New York City where Yuri worked as a graphic designer and Mike as a product designer. As Postalco, the Abelsons partner their individual strengths to produce finely-crafted products that have garnered them praise and devoted fans not just in Japan but around the world. We met up with Mike and Yuri at their shop in Kyobashi, a sober, no-funny business neighborhood wedged in the shadow of Ginza, Tokyo's commercial bright star. The shop is a fully-realized distillation of Postalco's elegantly utilitarian sensibility; their complete product line is displayed alongside office supplies, art projects, and a small library of reference books and curiousities. At first the shop might appear to better fit in high-end Ginza -- Postalco is not cheap --but its presence in a decidedly workmanlike neighborhood on the fourth floor of a faded office building is, to us, a quiet testament to more humble concerns. And in the end, it's the kind of place you enjoy looking to find. Later on we visited their office/studio in Kobama, a leafy neighborhood only a few train stops from Shibuya yet where the thin-air cluster of Tokyo's high rises recedes quickly into a distant memory. The contrast in settings between shop and studio seems to highlight a good balance in their approach to work: their ability to unify what they want with what they do and to craft a lifestyle that works. It's nice. We talked with Mike and Yuri about issues of craftsmanship and why they run their business in Japan. Postalco has always struck us as a perfect Japanese company: simple forms that belie obsessive attention to details and quality, masking intricate design considerations and construction challenges. While they've been expanding their presence in the United States, Mike and Yuri spoke at length about how living in Japan is important, if not vital, to the success of their company. For us, each time we visit Tokyo we wonder how we could ever figure out a way to move to that city we love. What makes Postalco so perfect for this WORKING series is the way Mike and Yuri have answered this question: by pursuing their interests so resolutely that they've had little choice but to do what they want. Mike and Yuri show that by concentrating and perfecting the skills you have can very well lead to broader horizons, new lessons, and richer experiences -- the kind of life you want. Yeah. |

|

| Postalco's website |

KNEE HIGH MEDIA JAPAN |

|

Knee High Media Japan is a magazine publishing company in Tokyo owned by a husband-wife partnership, Lucas Badtke-Berkow and Kaori Sakurai. Founded in 1996, Knee High's first magazine was TOKION, a highly regarded and influential publication that spotlighted Tokyo's burgeoning youth culture while considering the outside world from a compelling we-are-on-the-same-team perspective that effectively kickstarted the trend of product collaborations between businesses we still see today. Since then, Knee High has branched off into new publishing directions, beginning with family (MAMMOTH - est 2000), travel (PAPER SKY- est 2002), Tokyo subway commuting (METRO MIN - 2002-2003), and plants (PLANTED - est 2006). In addition to their independent publications, Knee High also offers a consulting service (KNEE HIGH CREATIVE) to other businesses, helping clients set up magazines and catalogs infused with Knee High's singularly syncretic sensibility. We've long admired Knee High's work and even while we were disappointed when PAPER SKY ceased its bilingual text we continued to buy each new issue. Knee High's publications always include some of the things we love best about Japanese magazines: intriguing photography, fresh design, and the enthusiastic curiousity of the hobbyist coupled with the organizing mania of the expert. But most of all, the unwavering spirit that guides Knee High's work is the sense of mutual interests the magazines share with its readers. Knee High always manages to avoid the cliquish elitism that dooms other magazines, perhaps because it lacks cynicism and self-importance. We've always perceived the editorial focus of each magazine to be narrow, sharp and deliberate: clearly their aim was not growth in terms of market share but something more personal. While Knee High's magazines will never dominate the mass newsstand, they instead help to define the terrain they operate within, raising publishing standards by focusing inwardly on quality and excellence in the pursuit of idiosyncratic interests. They produce the kinds of magazines we love to read, even if we can't read them. We visited Lucas and Kaori at Knee High's office located in a converted house in Shibuya as they were winding down for the new year holiday. They have the rare good fortune to possess a garden where they cultivate herbs and vegetables and relax under maple and persimmon trees where the noisy mejiro, a lovely white-eyed green bird, feasts off the last of the year's fruits. We were especially interested in listening to their experiences as partners running a small business in Japan. |

|

| Knee High's website |

CETMARACKS |

|

Cetmaracks is owned by Lane Kagay who began manufacturing front-end cargo racks for bicycles while messengering in San Francisco. Initially Lane used his welder to repair iron gates in San Francisco but soon realized that this line of work would lock him to a city he wasn't sure he wanted to live in forever. In 2007, Lane moved to Eugene, Oregon, a town famous for its "alternative" lifestyles, which for him meant somewhere cheap enough to pursue his interests yet creative enough to support them. Cetma embodies the best of small business. Adhering to no kind of business model, Cetma follows an organic growth pattern where yesterday's needs determine today's activities. In an era where "sustainability" has been sadly relegated to the marketer's lexicon, Cetma creates a product that comes from a personal need predicated on the idea of living a life that supports itself. We were especially interested in learning about Cetma since Lane actually makes something. For all the talk of offshoring American manufacturing, its heartening to see that manufacturing and production of real goods continue in places like Eugene. Perhaps someday a large foreign company will produce bicycle racks with an economy of scale that severely undercuts Cetma's pricepoints, driving Cetma out of business. But that day seems unlikely since the demand for these racks are fueled by people who ride bicycles, not cars. And unless there's a large shift in the general population to bicycle commuting, a small business like Cetma appears safe from corporate predation. We root for these companies that produce goods -- tools -- for specific people and communities, who practice and use and need what they make. |

|

| Cetmaracks' website |

CAUSE & EFFECT |

|

Cause & Effect is a post-production studio in New York City owned by Jason Zemlicka and Jamie Hubbard. Their work runs the gamut of commercial broadcast spots to music videos to what is called "branded content" (don't ask us what that means). Drawing heavily upon the large media conglomerates headquartered in the city for their client base, Jason and Jamie have created a business in a competitive industry already saturated with talent, reward and heartbreak. What distinguishes Cause & Effect from other post houses, though, is not only their intense devotion to client needs but their individual personality traits that together create a workplace that is friendly, fun and inspiring. Simply put: they are really nice guys. We visited Cause & Effect's Chelsea studio as they were busy expanding their office space and talked with Jason and Jamie about what motivated them to leave the relative security of their previous jobs to break out on their own. As talk of recession and a Global Financial Crisis dominated the airwaves, they spoke candidly about running a small business, independence and risk taking. Every business venture is at the start a calculated risk; Cause & Effect, however, spends less time calculating, instead following their gut instincts that so far have led to success. For them, in the end, the possibility of doom is preferable to the status quo. |

|

| Cause & Effect's website |

MYORB |

|

MyORB (My Orange Box) is a graphic design company run by Lucie Eder based in New York City. The "orange box" in its name refers to a design school project of a literal orange box used to distinguish Lucie's portfolio from the ubiquitous black. Today, this drive for distinction continues to underscore the work of this small design studio. In its own quiet way, MyORB works assiduously with its clients to produce clear graphic information that help clients best understand and express their own identity. In fact, MyORB's chief strength is identity development, championing the belief that good design can be both revelatory and transformative. We spoke with Lucie at her office in SoHo about independence and self-determination and how these values struggle at times for control over a small business. We were interested to see how a small design company operates in a city full of designers where clients have a wide range of studio options, from large multi-national offices to desktop amateurs with budding design aspirations. We were impressed with the way MyORB's client list has evolved -- nearly entirely word-of-mouth recommendations, which indicates not only client satisfaction but also a kind of informal affinity network of small businesses, the kind of network we admire and seek to support. |

|

| MyORB's website |

KIOSK |

|

Kiosk is a kind of general store if the world could be seen as a small town. Owned by a married partnership, Alisa Grifo and Marco ter Haar Romeny, Kiosk features a rotating exhibition of everyday products from around the world, smartly selected with an eye towards craftsmanship and singularity. "Their beauty," Kiosk writes in its mission statement, "is sometimes hard to see in today's market; our motivation to start Kiosk was to shed some light on these anonymous objects and support independent producers." In a retail world of endlessly repetitive consumer choices, Kiosk celebrates the child-like joy of discovery all too often lost in the anxious marketplace. One of Kiosk's defining characteristics is the boosterish positivity underscoring each selection, most directly evident in the often personal mini-stories Alisa writes to introduce each product. We were greatly impressed by Alisa and Marco's enthusiasm for the manufacturers they've met and come to represent in the SoHo shop. In thinking about their space as a kind of museum they solve at least two problems of traditional museums and other "curated" stores. First, they tackle the museum's static, proprietary displays by offering a wide price range of products anyone can afford to take home (not just a souvenir but the actual thing). And second, they avoid fetishizing products by emphasizing the humble utlitarian aspect of well-made and well-designed goods. After all, a dustpan no matter how exquisitely crafted is in the end just a dustpan. Nothing precious here. We were curious to hear about Kiosk's struggles to survive in a neighborhood we seldom visit anymore after the arrival of so many chain stores and outside businesses that have little interest in downtown. Kiosk is the kind of business all too often mourned with gauzy nostalgia when they close in the face of rent increases or online competition. That it survives in the heart of one of the world's fiercest retail centers ought to call out all those who support the little guy since Kiosk stands as a friendly yet determined advocate of the personal. It is a place you remember long after you visit. |

|

| Kiosk's website |

THE DISPENSATION Before it all gets wiped away, let me say, there is wisdom in the slender hour which arrives between two shadows. It is not heavenly and it is not sweet. It is accompanied by steady human weeping, and twin furrows between the brows, but it is what I know, and so am able to tell. |

ACROSS FROM WESTERN CITY |

A ROLLERCOASTER IN WASHUZAN |

THE ECSTASY OF TRANSCENDENCE The sweetest man in Tokyo. |

TOMITY Tomity profiles Toshihiko Tomita, a professional track cyclist living in Tokyo, Japan, as he embarks on his 25th year as a Keirin racer. Keirin cycling is one of Japan's most popular gambling sports in addition to being one of two original Japanese athletic contributions to the Olympic Games (along with judo). This short documentary surveys the sport of Keirin as Tomity reflects upon his long career and considers life after professional cycling. A de facto ambassador of Keirin, Tomity is perhaps the most visible promoter of the sport to fans of track cycling living outside of Japan. |

TOKYO SKIDS Fast and furious skidding, Carnival style. |

TOM CRUISER Where are you going? |

PUBLISHING:

After Modern History: About the Series

|

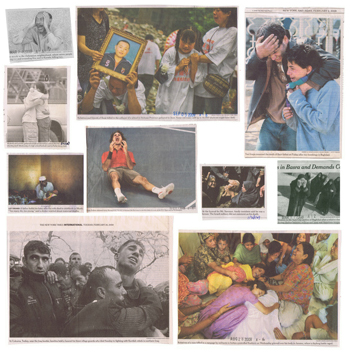

AFTER MODERN HISTORY is a series of newspaper clippings that looks for patterns and typologies in photographs, re-imagining the paper as a site of affinities instead of as isolated cases of bad news. If the newspaper is the first draft of history, AMH is a re-edit, another draft that tells a more coherent and empathetic story about humanity by emphasizing the universal -- what ties us together -- and rejecting how the daily paper spotlights distinction and atomizes its subjects. The best news photography illustrates the essential element of the story it accompanies. AMH changes that story by rescuing, for example, the mourner from the news of the day and placing him alongside others who’ve experienced similar grief. For most people caught on the hard end of luck, the newspaper can be a lonely place. AMH is an attempt to close the distance between the paper’s subjects as well as between the reader and those subjects by removing the glad-it’s-not-me response to tragedy and misfortune. After all, sooner or later that news may very well happen to us. Each collection of clippings is published as individual, pocket-sized books. Special thanks to Sarah Charlesworth. For ordering information, please send an email here or contact the distributor below. |

|

Distribution: Textfield (North America); Motto (Europe) |

|

|

| LINES 48 pages, 4 x 5.75 inches, offset, b/w interior, 1/1 cover, perfect bound, 2011 Collection of newspaper clippings of people, animals and things in linear order. Part of the series, After Modern History. Printed in New York City. |

|

|

| WEEPING 48 pages, 4 x 5.75 inches, Risograph, b/w interior, 2/1 cover, perfect bound, 2009 Collection of newspaper clippings from the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal of people crying. Part of the series, After Modern History. |

|

|

| BICYCLES 48 pages, 4 x 5.75 inches, offset, b/w interior, 1/1 cover, perfect bound, 2009 Collection of newspaper clippings where bicycles appear incidentally to the photograph's subject. Part of the series, After Modern History. Printed in New York City. |

OTHER:

About

|

|

“So, we should take Cascade Express, go down Gulch, stay to the right and when it veers close to Boulevard, duck down the unmarked trail. That’s Exro’s, I think.” “Sounds good.” They board the lift, a wide quad chair that skims swiftly along the mountain’s rise. He folds the trail map and sticks it back into his chest pocket, removing in turn the small flask of whiskey he nips from in order to relax. Okay, slowly now: deep chesty breaths of fresh air, exhale. The dense clouds which obscured visibility all morning long begin to part, opening up the mountain to the sky and the sun that later will cause them to shed layers in the afternoon’s warmth. For now, though, it’s all good – “epic,” he catches himself muttering to no one in particular. They sit mutely, transfixed by the revelation of the volcano’s snow-capped peak looming up ahead like a gloved fist. At the summit, they plop down onto the hard-packed snow to strap into their boards, each still lost in the reverie of the ascent. When they finish, they look at each other and speak for the first time since catching the lift at the mountain’s base. “Uh, which way were we supposed to go?” Left or right or straight? “Um, shit, I don’t remember." |

|

|

General inquiries: mail[at]tramnesia.com Book distribution: Textfield (North America), Motto (Europe) |

|

![]()

TRAMNESIA 2007–2012